by Mary Liepold

In March of this year, I joined a beautiful blue bus full of other eager learners on the 2023 Maryland Civil Rights Education Experience, an 8-day tour with 13 stops in North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee. I was extraordinarily moved by what I learned. I am writing to share a few takeaways and one indelible image, to encourage others to join next year’s Experience, and to make a public commitment to anti-racism.

Two local civil rights heroines traveled with us: Willie Pearl Mackey King, from my very own neighborhood, who worked closely with Dr. King and typed his historic Letter from Birmingham Jail, and Joan Mulholland from Virginia, who spent two months on death row in Mississippi’s infamous Parchman Prison for taking part in the Freedom Rides.

I’m a passionate reader, and I came of age in the 60s, so I knew the general outlines of civil rights history. I already knew, for example, that it stretches back long before the 60s. Like many of us, I have stepped up my learning in recent years. I have learned that we are in racism like fish are in water. And I have resolved to be not a guilty bystander, but an ally.

Reading history is one thing. But standing in the places where it happened and talking with participants made the ugliness of racism and the beauty of nonviolent resistance profoundly and personally real. Thousands of significant details coalesced to reinforce what I already knew about effective, nonviolent human rights work – and its cost.

We saw the importance of ordinary people, including women and children, alongside leaders like Dr. King and John Lewis. There was Joanne Robinson, an English teacher who stayed up night after night mimeographing flyers to publicize the bus boycott. And Hezekiah Watkins, who was arrested at 13 for trying to learn more about the freedom rides and sent to Parchman, while his mother wondered whether he was dead or alive. And Bob Graetz, a white Lutheran pastor who worked closely with King and whose parsonage was bombed three times.

We also saw the importance of allies from other parts of the U.S. – aka “outside agitators” – in a movement necessarily led by those most affected. As a white person, I felt my heart lifted by stories of others who heard the call and joined the cause, often at great cost to themselves.

Some might have said it wasn’t their struggle. Lilla Watson, an Indigenous activist in Australia, famously said, "If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together." Joanne and Hezekiah and Bob knew, with Dr. King, that we are all bound up in the same garment of destiny.

We encountered a bit of Catholic history too, on the Civil Rights Trail. The last of four planned overnight stops, on the 54-mile walk from Selma to Montgomery, was the City of St. Jude, a 36-acre Catholic school and hospital complex belonging to the Archdiocese of Mobile. Founded in the 1930s to serve the poor, especially African Americans, it included the first integrated hospital in the Southeast. Viola Liuzzo (a better-known white ally) had died there on March 25, 1965, after she was fatally shot by a Klansman.

Some 2,000 marchers camped on its rain-soaked athletic fields in April, a few weeks after Liuzzo’s death, and heard Harry Belafonte, Sammy Davis Junior, Leonard Bernstein, Odetta, Mahalia Jackson, Johnny Mathis, Tony Bennett, Joan Baez, Nina Simone, Dick Gregory, Pete Seeger, Shelley Winters, Frankie Laine, Billy Eckstine, and Peter, Paul and Mary, among others, in a concert on the grounds.

The donations that supported the work of St. Jude dropped so sharply after the march that it struggled for decades to stay open. Donors who had been willing to support its charitable work were apparently less interested when it stood up for human rights. The parish is still active, there’s a center that provides loving care for children with special needs, and the hospital has been converted into apartments for low-income seniors.

My third top takeaway was the importance of the arts to the movement.

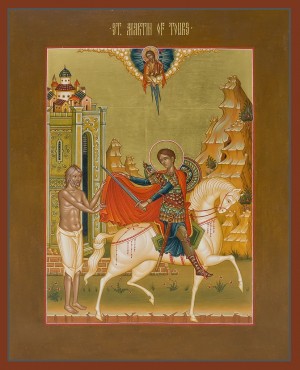

You have all heard of Birmingham Sunday, September 15, 1963, when KKK members murdered four young girls during a church service. Joan Baez’s version of the Richard Fariña song about it has been stuck in my head for 60 years. But on the tour I saw the Wales Window. (Photo credit: Solomon Crenshaw, For The Birmingham Times, https://www.birminghamtimes.com/2018/10/the-iconic-wales-window-inside-16th-street-baptist-church/)

You have all heard of Birmingham Sunday, September 15, 1963, when KKK members murdered four young girls during a church service. Joan Baez’s version of the Richard Fariña song about it has been stuck in my head for 60 years. But on the tour I saw the Wales Window. (Photo credit: Solomon Crenshaw, For The Birmingham Times, https://www.birminghamtimes.com/2018/10/the-iconic-wales-window-inside-16th-street-baptist-church/)

When images of that day’s death and destruction made international news, a Welsh artist named John Petts offered to replace the church’s shattered stained-glass window. Because he wanted his art to be a gift from the entire nation of Wales, and not from its government or a few wealthy magnates, donations were capped at 15 cents in today’s money. Thousands of Welsh adults and children lined up to donate, and the window was completed and installed in 1965. I love this image not only because of the international solidarity and the beautiful bronze Black Jesus, but because his gesture expresses the core of nonviolent activism. One hand says STOP what you are doing, stop the injustice, while the other recognizes the opponent’s human dignity: You too are a child of God. We can work together for a better world.

This window and the hope it inspires was the high point of my Civil Rights Education Experience. I hope you will contact the Montgomery County Office of Human Rights, board the bus next year, and discover your own. And I ask almighty God for the grace to carry what I have learned into action under the direction of God and my sisters and brothers of color, especially the descendants of slavery.